Brother Anselmo does what he can with what he’s given, which is why it’s not my fault, and certainly not his, if the bell didn’t go off as usual.

Well, not the bell but the cell phone….

Which is just the problem, isn’t it? First of all, in any normal monastery, some friar would slip reverentially over to the bell tower, find the rope, and give it a good yank. But here it’s a little box that sucks the life out of the wall each night and then buzzes or plays jingles. Whatever it does, it’s supposed to do it at 6:30, when I’m supposed to wake up. It doesn’t do it again until 7:05, when I have to leave the house. And today the little box decided to sleep in (as did I) and only get going at 7:05.

That’s it—Brother Anselmo gets me out of bed, because I couldn’t do it by myself. I wake up with two certainties, which fall like fire curtains into my day: my marriage of 42 years is over, and my country is gone. There is no reason whatsoever to get out of bed.

There’s no reason to stay in it, either. And if I stay in it, I will be depressed. So I invoke Anselmo and he gets me out of bed. It’s not that he wants to—he actually doesn’t think much of me—but he has to. He has to do all this shit because he is the perfect monk, in my head. And even though my head is a late 20th century / early 21st century head, Brother Anselmo is still back in Bec, Normandy in 1066 or so. Brother Anselmo is still a monk, not yet the Archbishop of Canterbury. He was dealing with annoying monks, even so, and some perhaps were even worse than I.

A notable opponent was a young monk named Osborne. Anselm overcame his hostility first by praising, indulging, and privileging him in all things despite his hostility and then, when his affection and trust were gained, gradually withdrawing all preference until he upheld the strictest obedience. Along similar lines, he remonstrated with a neighbouring abbot who complained that his charges were incorrigible despite being beaten "night and day". After fifteen years, in 1078, Anselm was unanimously elected as Bec's abbot following the death of its founder, the warrior-monk Herluin. He was blessed as abbot by Gilbert d'Arques, Bishop of Évreux, on 22 February 1079.

When your marriage is over and your country has gone away, you need an abbot like Anselmo, and at times like Anselmo’s abusive fellow-abbots. You need to be beaten, occasionally, which for me is nothing worse than being trapped (by my own doing) in my cell, while the life of the monastery continues without me. I stay home, I do not get out of bed, I suffer.

I summon Anselmo each morning because I know this. There is, in modern-bound books, that weakest joint, the hinge. It’s nothing but a piece of paper, usually, and it keeps the whole thing together. Until it breaks, and everything falls apart. The first ten minutes of every day are that hinge for me.

Fortunately, Anselmo is an old man, too, after these 1000 years plus of his existence. He doesn’t tell me that I’m lazy and idle—but wasn’t that my bladder, only half-full but suddenly growling to be taken to the bathroom? Yes, and since I’m there, I take my medicine, because I might forget later on.

Then I go back to the bedroom and make my bed, because that’s what I do every day. Brother Anselmo says nothing, since what is there to say? Today, the bed is filled with lumps and the top sheet isn’t actually tucked in, but that’s not the point. The point is that having the bed nominally made will leave me with nothing to do, so I’ll have to get down on my knees and pray. I do that too, though I’m an atheist. But I’m also a drunk, and for eight years I haven’t had a drop. So that’s a miracle and I get down on my knees, since even atheists can still be grateful. Anyway, I also feel better after I pray, and God doesn’t seem to mind.

Brother Anselmo is looking at all this with pursed lips—you can tell he could let out a few telling words, in Medieval French, Church Latin, or Anglish, a word that neither I nor my computer seem to know. It’s what I would call Old (or Olde) English. The point is that Anselmo could let me have it in several tongues, but he’s smart enough not to. I’ve moved on to making coffee, he observes, and I’m putting clothes on, and shoes, even, and that means I have every chance of getting out the door and pointing myself towards the bus station. Brother Anselmo sighs when he hears me lock the door to the apartment and open the gate to the sidewalk outside. He turns, then, to go back to the bedroom, with its badly-made bed. He puts the broken marriage in the closet by the blanket a friend used while going through status epilepticus for a couple of days. The country is gone, of course—nothing to be done about that.

Brother Anselmo should be in the scriptorium, of course, but that’s gone, too. Or rather, it may never have been, at least not the way we think of it, or want it to be. Certainly the way I want it to be—because I believe in what used to be called Western Civilization. It’s the glorious history and creation of straight white men standing proudly on the bleeding, scourged backs of women, non-whites, and the rest of the world. But that civilization (or Civilization) was pretty special.

There’s Suetonius, for example. I know nothing about him, except that he’s the guy who everybody reads, when they want to know what the Romans were really up to. I’ve known about Suetonius for years, and even though I took Latin in college, I never read him in either Latin or English. I never read the other historians like Livy and Tacitus, either, but they always occupied a higher shelf, somehow, than Suetonius. Actually, Suetonius barely spends any time in the library on any shelf, the Romans are always coming in to grab him before going off to the beach. He’s got the low-down on everybody, does Suetonius, and is just dying to tell you about it.

But if Suetonius is going to be around at all—in the library or loafing on the beach—somebody is going to have to write, and that means WRITE. Not what I am doing, sitting at this little table in an air-conditioned room with sugary snacks beckoning me. I am sitting at the table and tapping at the flat thing that we all carry with us, and the inside lid of the box is making words, that are indeed what I intend to say.

Just not what I want to say.

What I am doing has nothing to do with writing, of course, though I think it does. Anselmo would be astonished—I can hit a button called “Enter” and the little words that I think I see (they’re not—they're zeroes and ones) well, the words vanish. To “Enter,” it seems, is to vanish. But what to make of that button Enter, which also says Return? Must you Enter to Return? And what does that really mean?

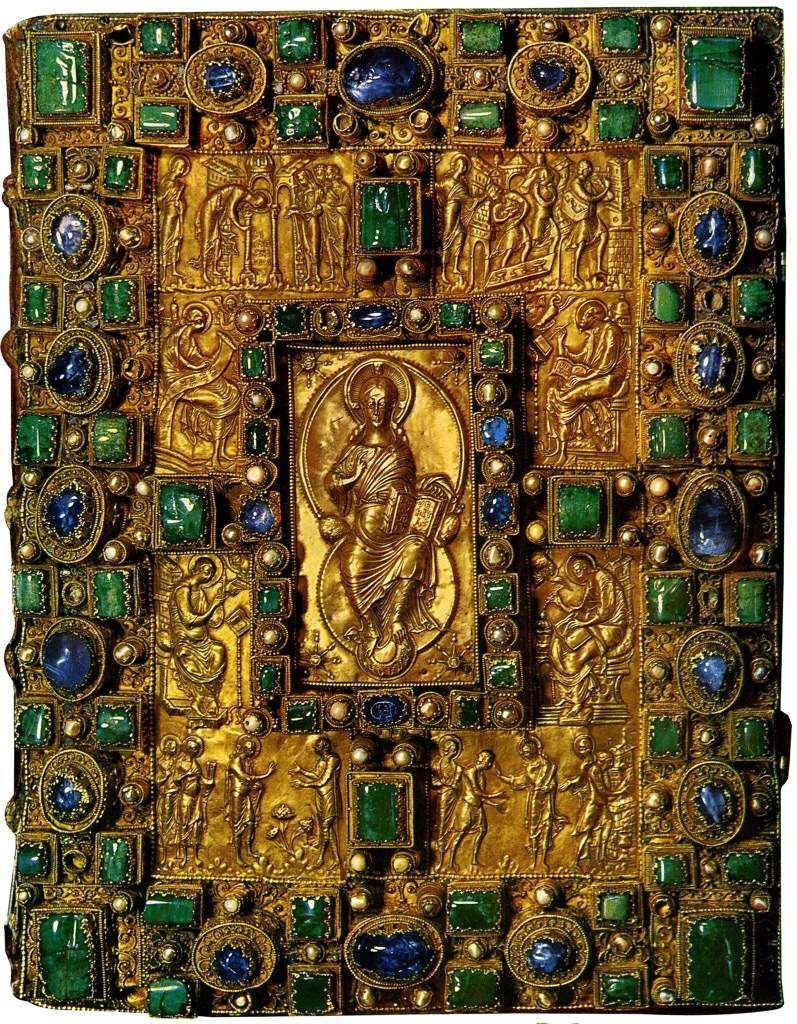

I can think of this, but Anselmo cannot, because he needs the calves to grow, dammit, since the book that William the First (formerly Duke William of Normandy) wants has to be written on something. And that parchment comes from vellum which is nothing but a baby cow that has grown big enough to taste good (for the muscle) and to write books on (for the skin). The book that William I wants may be covered in gold and decorated with jewels. It may even look like this:

Well, if Anselmo is going to produce a work like this, he’s gonna have to get busy, which means he has to roust up that damn monk, Osborne, who even though reformed is no saint. Neither is Anselmo, at this point, which is probably fortunate. There’s a bit of sinning to do on the road to sainthood, which is why the only hide getting tanned is Osborne’s, not the calves—which are Osborne’s responsibility.

So Anselmo forgets going to the scriptorium which is, anyway, not there, and gets down to the barn where Osborne should be feeding and caring for the damn calves. One calf can produce about three and a half sheets of vellum, which means that the process of turning live animals (with their stupid love of their mothers, even if she’s a cow) into something bearing the word of God is long. It involves a lot of cold water, too, which is lousy on the hands.

It also stinks, since part of getting a calf from an animal into a book means stacking the hide, letting it soak in limewater (not the lime of gin and tonics), and letting it putrefy. Well, that’s what I call it, since I lived in Chicago in the 1980’s when there was still a stockyard and a tannery in the city. At some point, the hides are piled up on top of each other, and the whole thing is a mess. It smelled completely revolting, even half a mile away in a good part of the city.

We send off our dead calves to be made into bags for rich women to carry, but Anselmo has another goal. The calves are for the word of God, though what William I wants is the words of Suetonius…and really?

Really?

You’re going to kill an animal to get three and a half pages of skin that you will call “vellum,” on which a malnourished and sleep-deprived monk with a bad back from bending over the desk in the scriptorium that doesn’t exist—just to write the words of an infidel named Suetonius? That little calf frolicking in the fields of the Lord met his death for THAT?

Anyway, Anselmo stands thinking just for a moment in my bedroom. I am pointed toward the bus station and the bus or the chariot is waiting for me. (I know this, and suspect that the bus is a chariot, since the guy who drives the thing is a monster, since he is blowing great clouds of smoke out of his mouth.)

Well, there’s no going to the Scriptorium, since it doesn’t exist, and I could have told Anselmo that, since I’ve a read a book called The Medieval Sciptorium: Making Books in the Middle Ages. In fact, the author of the book, Sara J. Charles, dispelled the idea that Brother Anselmo got up and went to work at the Medieval Scriptorium at all. The monks were in their cells, writing their manuscripts, all right—but that beautiful, long, silent room, lit only by an austere northern light in which the monks toiled endlessly and piously, preserving the word of God for you and Western Civilization for me….? That probably didn’t exist.

Still, it didn’t keep the author from writing a book about it, which in fact she did. And I read the book, though I also didn’t, since it wasn’t a book (no vellum, no papyrus, no clay tablets, not even paper). It was what might have been a book, if anybody had thought it worthwhile to find that damn Osborne, who should be tending to the flock or at least pondering the lilies of the field. But I read the “book” on the inside cover of another box that sucks its life out of the wall by my bed. The kind of box that has the Enter and the Return button.

My e-reader doesn’t have, perhaps, the faint smell of an animal whose skin has been soaked in calcium hydroxide. It also doesn’t need the dull blades and the icy water that will “scud” across the flesh. The only thing I might see on my computer screen is dust—but the vellum will have the pores, still, of where the calve’s hair stood, as it leaned against its mother, in those early days of spring.

The cover of the book can be turned and forgotten immediately—there’s no lapis lazuli to be wrenched from the ground and carried over the treacherous mountains of Afghanistan. The filigree holding the emeralds—how light and fugitive it is! And even the hammered gold will lose its luster.

I don’t have such a book as the one I’ve shown you, and perhaps neither did Anselmo, since he was in Normandy and in England, not in Germany, where the Codex Aureus of Emmerman currently lives. But if William I wants his copy of Suetonius, Brother Anselmo is going to have to shake down Osborne, in whatever non-Scriptorium he’s loafing in. And if I want my words to enter and return, I’m going to have to get out of bed to do it.

I think we both yearn for the Scriptorium.

No comments:

Post a Comment